This get a bit technical, but in short, the Ninth Circuit judges, usually known for their very liberal rulings, have opened up the possibility that the vaccine manufacturers could be sued. The blanket legal protection they had been promised was for a vaccine defined as preventing people from catching a disease. What they delivered was a treatment that made the symptoms less troubling. As a treatment, the legal immunity has been deemed to be void, leaving the door open for people who suffered adverse effects to opt for legal action against the manufacturers.

Wow. The Ninth Circuit decision in LAUSD gets it right. Plaintiffs can argue this is not a vaccine. pic.twitter.com/diXdg6euc9

— Warner Mendenhall (@MendenhallFirm) June 7, 2024

Last week, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeal issued an amazing ruling, reopening a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of COVID-era vaccine mandates.

Read the full ruling here: Health Freedom DEF. Fund_ Inc. v. Carvalho_ 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 13910

Initial Lawsuit – Threat of job termination.

The underlying lawsuit against LAUSD (2nd largest school district in the nation) was filed by Health Freedom Defense Fund in November 2021, challenging the constitutionality of the district’s March 2021 policy requiring employees to obtain the COVID vaccine (show proof) or be terminated. Read Health Freedom Defense Fund v. LAUSD Second Amended Complaint

Was the Vaccine Mandate Constitutional?

The legality of vaccine mandates is based on an old case from 1905 case, Jacobson v Commonwealth of Massachusetts concerning smallpox.

The Jackson court established that it is within the police power of a state to provide for compulsory vaccination. The Supreme Court in Jacobson upheld the constitutionality of a state compulsory vaccination law enacted to combat a smallpox outbreak.

The Court found that the vaccine mandate was rational in “protect[ing] the public health and public safety”. However, the Jacobson case does not stand for the proposition that anything goes in mandating vaccines.

Previous Courts’ Application of Jacobson is Wrong

In the context of the current pandemic (COVID-19), several courts have applied Jacobson to find that mandatory vaccine policies at state universities and among state executive agency employees meet the ‘rational basis test’.

In recent cases, plaintiffs have attempted to distinguish their cases from Jacobson by arguing that the COVID-19 vaccines are not vaccines but are instead “Gene Therapy Products” or that the mandates are not the result of a legislative process

The 9th Circuit today overturned a lower court decision that applied Jacobson. It said this:

“Addressing the merits, the panel held that the district court misapplied the Supreme Court’s decision in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905), in concluding that the Policy survived rational basis review. Jacobson held that mandatory vaccinations were rationally related to preventing the spread of smallpox. Here, however, plaintiffs allege that the vaccine does not effectively prevent spread but only mitigates symptoms for the recipient and therefore is akin to a medical treatment, not a “traditional” vaccine. Taking plaintiffs’ allegations as true at this stage of litigation, plaintiffs plausibly alleged that the COVID-19 vaccine does not effectively “prevent the spread” of COVID-19. Thus, Jacobson does not apply.”

They also said this:

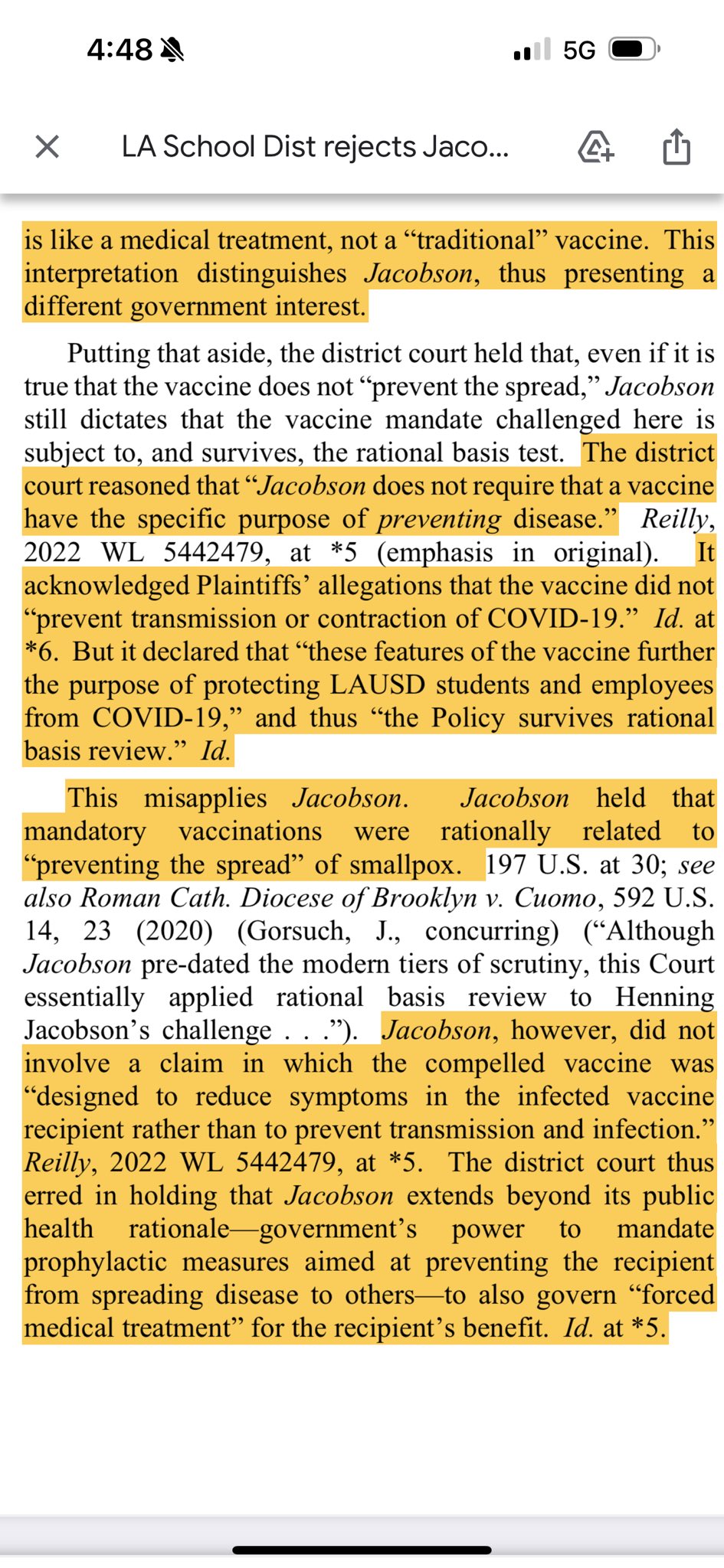

“This misapplies Jacobson. Jacobson held that mandatory vaccinations were rationally related to “preventing the spread” of smallpox. 197 U.S. at 30; see also Roman Cath. Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo, 592 U.S. 14, 23 (2020) (Gorsuch, J., concurring) (“Although Jacobson pre-dated the modern tiers of scrutiny, this Court essentially applied rational basis review to Henning Jacobson’s challenge . . .”). Jacobson, however, did not involve a claim in which the compelled vaccine was “designed to reduce symptoms in the infected vaccine recipient rather than to prevent transmission and infection.” Reilly, 2022 WL 5442479, at *5. The district court thus erred in holding that Jacobson extends beyond its public health rationale—government’s power to mandate prophylactic measures aimed at preventing the recipient from spreading disease to others—to also govern “forced medical treatment” for the recipient’s benefit. Id. at *5.”

Judge Collins, in his concurring opinion states “a competent person has a constitutionally protected liberty interest in refusing unwanted medical treatment.”

“The Court has stated that “[t]he principle that a competent person has a constitutionally protected liberty interest in refusing unwanted medical treatment may be inferred from [the Court’s] prior decisions.” Cruzan ex rel. Cruzan v. Director, Mo. Dep’t of Health, 497 U.S. 261, 278–79 (1990) (citing, not only Jacobson, but a series of later “cases support[ing] the recognition of a general liberty interest in refusing medical treatment”). In Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997), the Court explained that Cruzan’s posited “‘right of a competent individual to refuse medical treatment’” was “entirely consistent with this Nation’s history and constitutional traditions,” in light of “the common-law rule that forced medication was a battery, and the long legal tradition protecting the decision to refuse unwanted medical treatment.” Id. at 724–25 (citation omitted). Given these statements in Glucksberg, the right described there satisfies the history-based standards that the Court applies for recognizing “fundamental rights that are not mentioned anywhere in the Constitution.” Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., 597 U.S. 215, 237–38 (2022).”

“The Supreme Court’s caselaw thus clarifies that compulsory treatment for the health benefit of the person treated—as opposed to compulsory treatment for the health benefit of others—implicates the fundamental right to refuse medical treatment.”

Plaintiffs’ allegations here are sufficient to invoke that fundamental right. Defendants note that the vaccination mandate was imposed merely as a “condition of employment,” but that does not suffice to justify the district court’s application of rational-basis scrutiny. See Lane v. Franks, 573 U.S. 228, 236 (2014) (“[The] Court has cautioned time and again that public employers may not condition employment on the relinquishment of constitutional rights.”).